In the depths of the rainforests of New Zealand’s rugged Southwest breeds one of the world’s rarest penguin species – the Fiordland penguin. New Zealand Maori call it tawaki or sometimes pokotiwha. While the latter term translates to “gleaming head” owing to its conspicuous yellow crest, tawaki has a considerably more mythical ring to it.

A Fiordland penguin or tawaki on its way to its nest site on Breaksea Island, Fiordland

The Maori names for most New Zealand bird species reflect their respective calls – such as kiwi, kea, kaka. While this is also true for the two other penguin species inhabiting the New Zealand mainland – the Yellow-eyed penguin or hoiho and the Little Penguin or kororā – the term tawaki originates from ancient legends.

In Maori mythology, Tawaki was a god that walked the earth in human form. Why Maori would name a small – it stands a mere 55cm tall – and rather cuddly penguin after a god may have many reasons. Legend has it that Tawaki’s fellow human beings did not realise he was a god until “he ascended a lofty hill, threw aside his vile garments and clothed himself in lightning“. Thinking about it one could certainly argue that the yellow crest makes for a convincing lightning costume.

It could also be that the notorious heavy rainfalls of the West Coast and Fiordland might have something to do with the naming: “In Maori myth, the god Tawaki caused the flood when he cracked the crystal floor of Heaven and sent the sky waters cascading downward.“

Tawaki inhabit the southwestern coast lines of New Zealand’s South Island as well as Stewart, Codfish and Solander Island in the South. The northernmost breeding colony is located at Heretaniwha Point at the western end of Bruce Bay in the central West Coast, while the last breeding pairs occupy nest sites around Port Pegasus at the southern tip of Stewart Island. The two extremes of the tawaki breeding range seperate less than 500km. However, the true coastline length tawaki have available for breeding is somewhere in the region of 1,500-2,000 km owing to the vast and deep fiord systems that riddle the aptly named Fiordland National Park.

The breeding range of tawaki

Unlike all other crested penguin species that breed in well-defined colonies with up to several thousand nests crammed into rather constrained areas, tawaki have evolved to be very secretive birds. Their nests are located in caves, rock crevasses, under tree logs and roots or almost impenetrable vegetation. This, combined with the fact that most of the areas they inhabit are very hard to reach, explains why we still know very little about the species.

Tawaki is presumed to be one of the rarest penguin species with current estimates of their population ranging between 2,500 and 3,000 breeding pairs; the population is suspected to undergo a continuos decline. However, the species’ preference to breed in extremly rugged and inaccessible terrain makes population counts a daunting task and more of a guesswork than a reliable assessment. So there could be more. But there could also be less.

Spot the penguin – a good example why counting tawaki is not the easiest thing to do

In comparison to other penguin species, we know very little about tawaki. Only a handful of studies have been conducted in the past 40 years, the most comprehensive of which was carried out in the early 1970s. Most of what we know is limited to the birds’ breeding biology, their nesting behaviour and the threats they are facing.

One of the few things we know: what a tawaki looks like when incubating its eggs.

Well, there is a whole bunch of different threats that tawaki have to live with. Let’s start with the threat we know the most about: terrestrial predators.It is important to know that New Zealand is an island country that for millenia was dominated by birds. The only mammal that ever made it here were bats. This changed dramatically a few hundred years ago.

Terrestrial predators

When the Maori arrived in New Zealand, they became the biggest threat as they took tawaki for food; the species cryptic breeding behaviour might be a direct result of this. However, it was with the arrival of the pākehā – the white man – that it really turned southwards for tawaki. In the 1800s the European settlers brought with them a considerable array of four-legged beasts some of them as pets (cats & dogs), some of them to breed for their fur (stoats and possums), and some by accident (mice, rats). All of these sooner or later started to roam the land and migrate to the remotest areas of the New Zealand mainland, preying upon endemic bird species many of which had lost their ability to fly, like the Kiwi and Kakapo. And penguins.

Cute, but deadly. Stoats are a threat for breeding tawaki on land.

Saying this, the fact that Kakapo is quasi-extinct as a result of stoat predation while there still are penguins, shows that the latter must certainly be more resilient. The fact that penguins can be quite pesky when attacked probably works in their favour. But regardless it is quite clear that New Zealand birds would be better off without any terrestrial predators. What’s more, unlike the terrestrial birds that “only” have to deal with land-based threats, penguins have to cope with threats while out at sea.

And these sea-based threats might be an euqally big, if not bigger problem for tawaki.

Fisheries bycatch – set nets

The industrialisation of fisheries in the 20th century brought with it an ever increasing amount of fishing gear in the water. Particularly, fisheries involving nets have become a substantial threat to seabirds. And in New Zealand, one particular type of fisheries starts to emerge as one of the worst things that can happen to penguins – set netting. Set nets consist of a single, stationary net wall that floats upright in the water column. Set nets can be brought out just below the surface, in mid-water or close to the seafloor. And while their main purpose is to catch fish, they are a lethal threat to any marine animal that gets entangled in them and more often than not drowns. Bycatch of marine mammals and seabirds in set nets is a serious problem in New Zealand and it is known that it causes significant mortality in Yellow-eyed penguins.

A sub-surface set net – hard to see and a significant threat to diving seabirds like tawaki

To which degree set netting impacts on tawaki we don’t know. On one hand, the observer programmes of this fisheries does not deliver reliable estimates of bycatch rates in the regions where penguins are affected. On the other hand, we don’t know anything about the foraging behaviour of tawaki, i.e. if their foraging grounds overlap with set netting regions, whether their diving behaviour makes them likely to end up in set nets.

Marine pollution

In recent years, New Zealand policy makers have turned towards a more liberal approach to mining operations. This comes in several facets which potentially impact tawaki. On one hand, terrestrial mining interests along the West Coast are substantial. On the oher hand, oil exploration in New Zealand waters has become a hot topic and, again, the West Coast is an area of considerable interest.

All this means that tawaki might have to cope with run-off pollution from terrestrial mining operations as well as potential oil spills. But again, we have no clear information whether tawaki forage in current or future “pollution danger zones”.

Ocean warming

The world’s oceans are getting warmer. This brings with it substantial change in marine ecosystems and decreasing oceanic productivity. Obviously these changes are likely to affect top marine predators such as tawaki. Yet, it does not need to be all doom and gloom. Despite the reasonably limited range of tawaki, the species inhabits immensly diverse marine habitats (more on that on the Project page). This might be an indication that tawaki are adaptable and able to adjust to new situations.

However, this does not mean that everything is indeed peachy.

First of all, we have no idea whether there is actually any truth to the idea that tawaki can somehow cope with ocean warming. And even if tawaki are super-flexible and can adapt to change, everything has its limit… and the more we know about such limits the more we can do to mitigate reaching this limit.

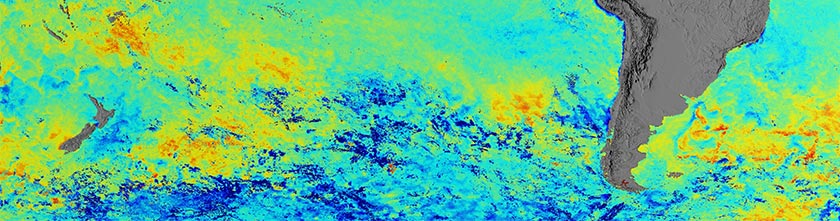

The heat is on in tawaki country: yellow and red indicate above average temperatures in February 2002

As mentioned before, we know very little about tawaki. And most of what we know about the species covers the terrestrial part of their biology. Yet as a penguin, tawaki spend most of their time at sea – and as such will be vulnerable to the multitude of sea-based threats like the ones discussed above but also threats we have no idea that they exist.

This is why the Tawaki Project sets out to find out what tawaki do while at sea, what affects them when they are in the water and how this impacts on their population in the long run.